How do you tell the difference between an American and a Canadian? Depends who wants to keep the largest undefended border in the world intact.

When I taught a course at York University on Canadian culture, my first year students would claim that Canada wasn’t different from America. So, I’d tell them the joke about Canadians and Americans that was making the rounds when America invaded Iraq in 2003.

An American border guard stopped a man with a dual citizenship passport to ask about his nationality. The man explained that he was a citizen of Canada and the US. “You can’t be both,” the border guard insisted. “Which one are you? American or Canadian?” The man repeated that he was a citizen of both countries.

The border guard grew increasingly frustrated. Finally, he had an idea. “If your country went to war, what would you do?” the guard asked. The man replied: “It depends on the war, and what it was about.” The guard was thrilled. “I knew it,” he said. “You’re Canadian.”

The border guard had a point. Canadians are skeptics and Americans tend to be well, more gullible. You could say our cultural differences divide us into scoffers and doubters versus dogmatists and true believers.

When George W. Bush wanted Canada to join the American war on Iraq, Jean Chrétien, our Canadian Prime Minister then, said he wasn’t sending Canadian troops into combat because he didn’t believe Iraq was hiding weapons of mass destruction. Many Canadians didn’t believe it either. And as everyone knows now, it turns out there weren’t.

Most Canadians I know admire America’s entrepreneurial spirit and enjoy American music, their books and films and television. Some Canadians like me even have Yankee ancestors who came over on pilgrim ships. But we’re far too skeptical to take Americans as seriously as Americans take themselves.

Consider the hype about American exceptionalism.

Get over yourselves, we tell each other when you’re not listening. How can America be exceptional when the cost of its healthcare system per capita is higher than anywhere else in the world? And yet American life expectancy, according to the World Bank, had a global ranking of 49th in 2022, and Canada’s life expectancy ranks 20th after Israel, the Cayman Islands and Iceland.

Canada has universal healthcare, and we’re proud it’s a human right.

That means we don’t shoot health insurance executives down on the street over our medical bills. Nor is health care our number one cause of bankruptcy, which is the case for American families, according to the American Bankruptcy Institute.

Unlike America’s underfunded public education system, ours isn’t tax based. That may be why Canada’s public education system ranks sixth in the world, according to U.S. News and World Report, while America’s is thirteenth.

Then there are America’s ultra-liberal gun laws, its mass shootings and abortion bans.

In Canada, abortion is a legal medical procedure but in the US, nineteen states ban abortion or restrict the procedure earlier in pregnancy than the standard set by Roe v. Wade overturned by the US Supreme Court in 2022. As for mass shootings, more than 488 took place across the US in 2024, according to the Gun Violence Archive. According to CNN, last year in the US saw eighty-three school shootings. Twenty-seven were on college campuses and fifty-six were in schools with kindergarten to grade twelve.

The American dream isn’t doing so well these days either. The World Economic Forum puts Denmark in first place for upward mobility. Canada is number six, and the US is a laggardly 27th. Fast-rising wealth inequality is higher in the United States than in almost any other developed country.

We’ve often heard the American homily about George Washington admitting he cut down the cherry tree because he refused to tell a lie. Yet president-elect Donald Trump is a serial liar who falsely claims that Canada owes the US $200 billion a year in trade exports.

All of these questions lead us to ask another: when Trump muses about Canada becoming the 51st state, what’s in it for us? Lousy healthcare? Loss of reproductive rights? Unsafe schools?

So, may I suggest we leave the largest undefended border in the world intact? And while we’re at it, can we drop the 49th parallel and adopt a more equitable dividing line instead? Give us all of the Great Lakes along with upper state New York, Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont. We’ll also take Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Minnesota too.

That’s fair, isn’t it? Because there’s one thing we’ve learned as your neighbour — if you don’t ask, you don’t get.

Article originally published on The Toronto Star – read on their website at https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/how-do-you-tell-the-difference-between-an-american-and-a-canadian-depends-who-wants/article_cf4c766c-cf72-11ef-b9f0-6b4f53a2d7b6.html

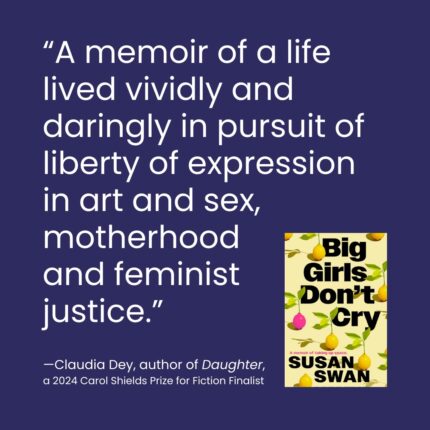

Live The Questions – Q&A for Big Girls Don’t Cry: A Memoir of Taking Up Space

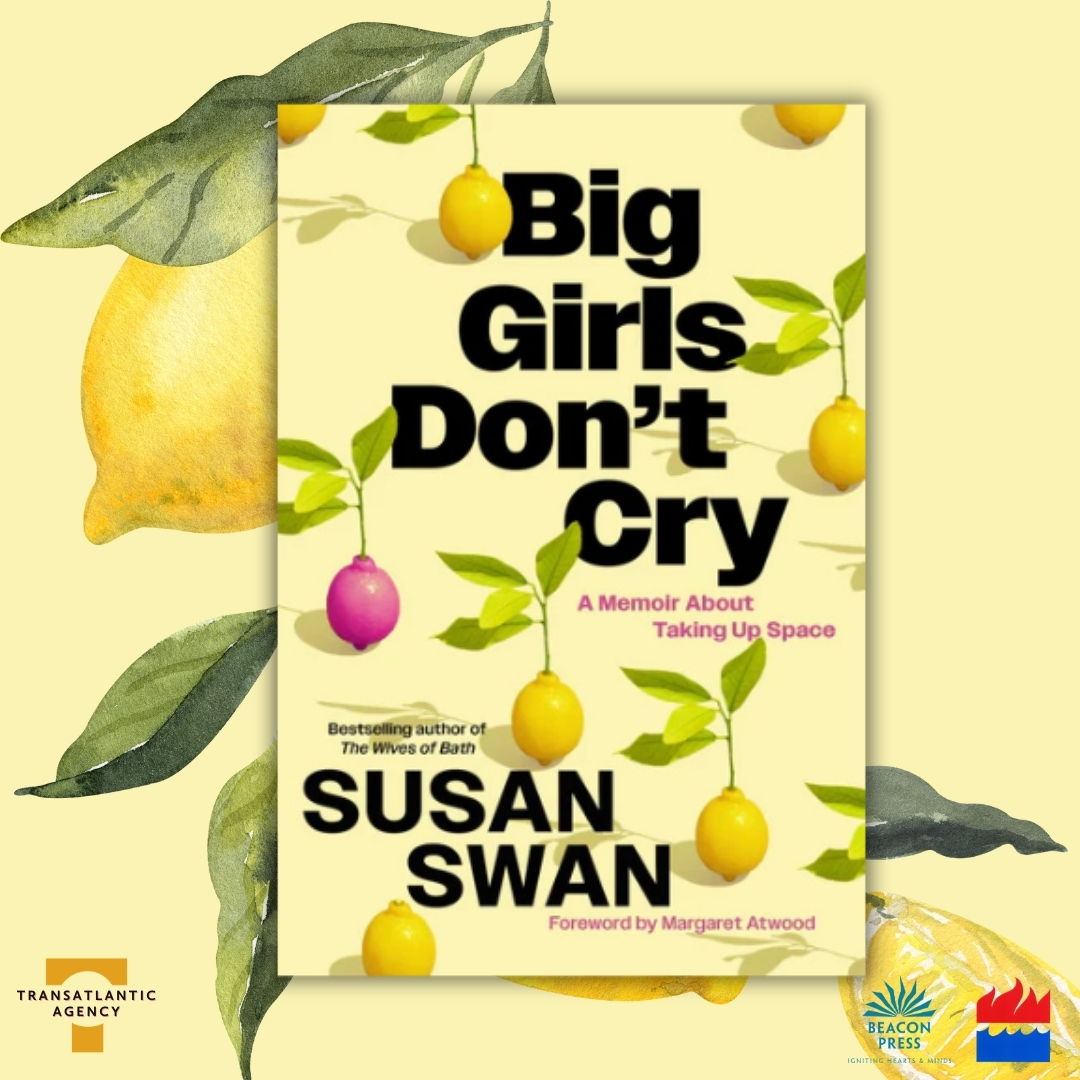

The Carol Shields Prize for Fiction (CSPF): We are so happy to be doing the cover reveal for your memoir Big Girls Don’t Cry: A Memoir of Taking Up Space. Was it hard to get the right cover? What inspired the image of lemons?

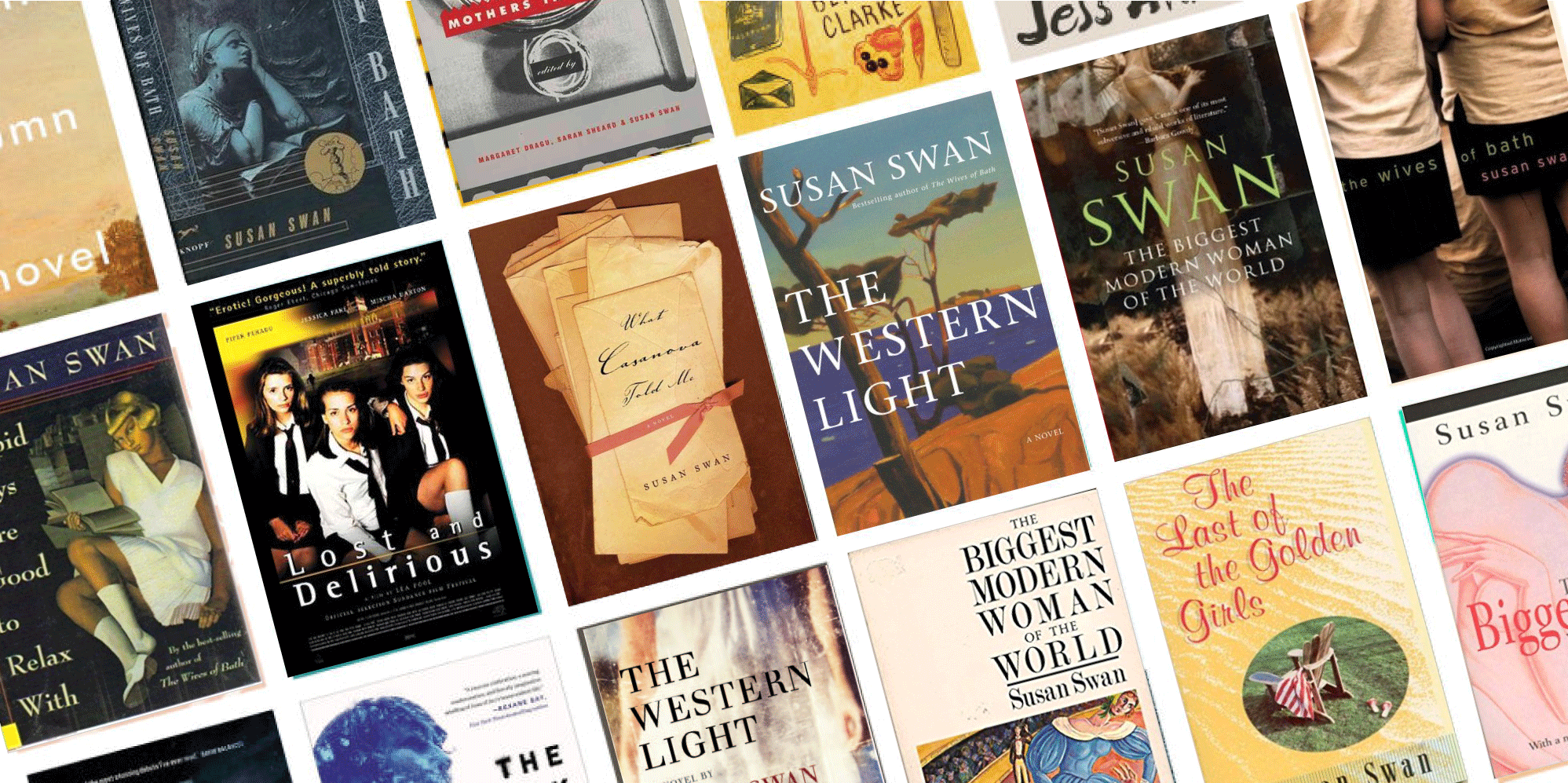

Susan Swan: Covers are like posters for your book. If you don’t get it right, fewer people will buy it, so that’s why editors and writers sweat over what works and what doesn’t. One writer I know went through 25 different covers before they were satisfied. That’s unusual but you get the idea. My memoir is about a big woman writer (me) coming to terms with difference and taking up space so the cover had to suggest something original instead of predictable images of tall female bodies that don’t quite fit the book cover. I wrote a novel about the real life giantess Anna Swan and a lot of covers for this novel show images like that. So we wanted to come up with something new. I’ll leave it to you to figure out what the pink lemon means.

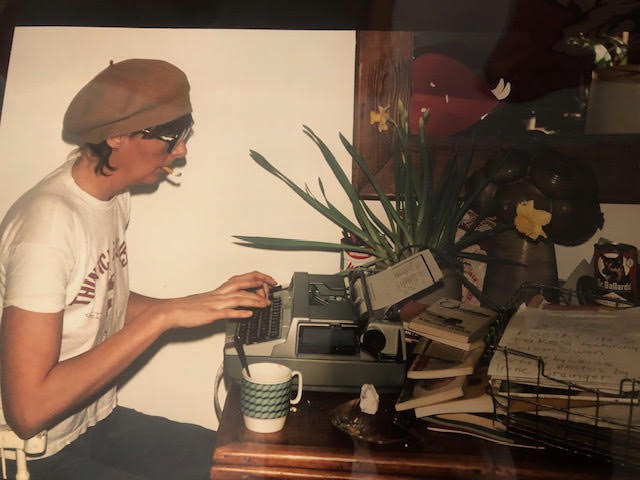

CSPF: How different is writing a memoir from writing a novel?

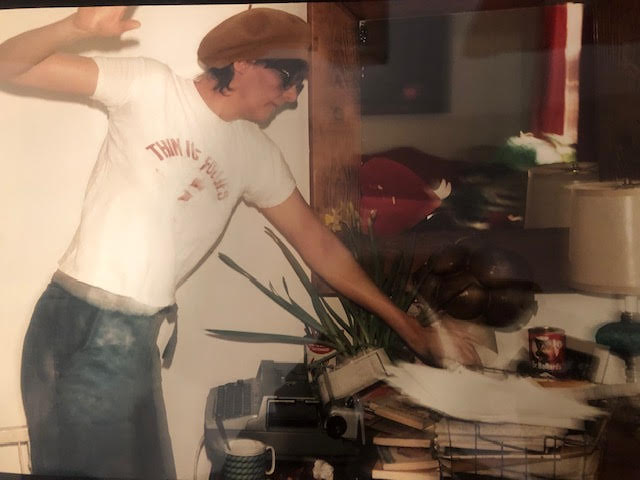

Susan: Not as different as you might think. Both forms dramatize and distill, so you need to write actual scenes instead of reciting a litany of events. I followed the same writing process that I use for a novel. Make notes; dictate a scene into my cell phone based on my notes; create a word document and revise endlessly. The big difference is the detailed way lawyers will check over your manuscript to ensure you aren’t compromising someone’s privacy. Although it’s rare, some novelists have been sued for defamation. Memoirs can be court cases waiting to happen.

CSPF: You said Big Girls Don’t Cry is about coming to terms with differences. Can you talk a little bit about that?

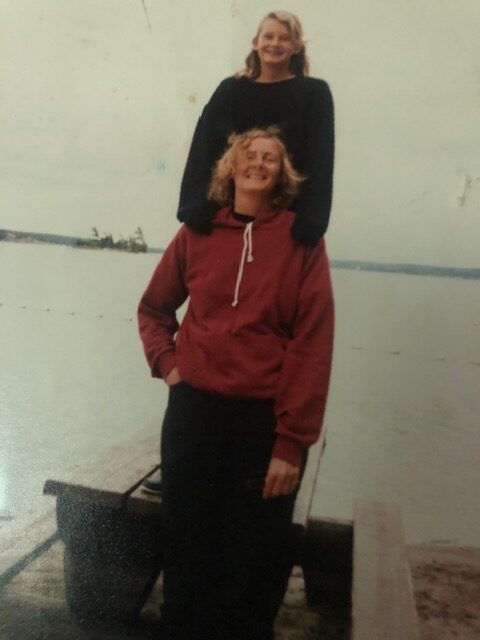

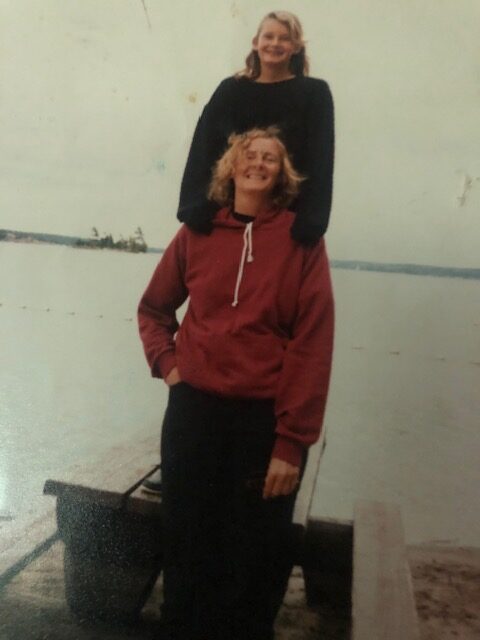

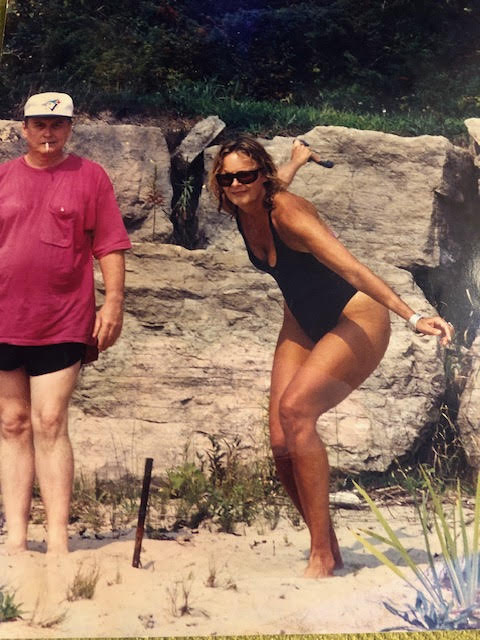

Susan: I was six foot two at twelve in the 1950s when women were supposed to be small and not heard. Things are somewhat better but very tall women still remain outside the norm. The novelist Jane Smiley recently pointed out to me that she and I are in the 99th percentile of North American women. We are one in 3000, in other words, and that means that others see us differently, and we see ourselves differently.

In the 1960s, I interviewed Femmie Smith, who used to sleep in a crib to try in vain to stop herself from growing, and who had four inches surgically removed from her thigh bones hoping it would make her more feminine. The Toronto doctor who performed the operation said he did it because she had been severely traumatized by her height of six foot two. Nowadays, a number of short men will request leg lengthening surgeries because they’re called derogatory names like “garden gnomes”, and short women say they are treated like children by their office mates. All these stories are in the memoir.

CSPF: Did you have help from other women writers with this book?

Susan: My friend Margaret Atwood suggested I write about my height and she read some very early rough drafts. At first, I dismissed it as a dumb idea but the more I thought about it, the more I realized my size had affected me powerfully without me being aware of it.

Early on, it made me feel I wasn’t feminine enough, and when store clerks would mistake me for a man (which still happens if they can’t see my face), I would just want to crumple up and die. As I got older, I learned height can be a dramatic tool that you can use to your advantage, which is why most giants become entertainers. If people are going to stare at you anyway, why not ask them to pay for doing it?

CSPF: Earlier you mentioned your 1983 novel, The Biggest Modern Woman of the World. Readers must often wonder whether there are any familial connections between you and the real-life Anna Swan, the Nova Scotian “giantess” you wrote a novel about. Is there a link?

Susan: I’ve researched our backgrounds and, aside from our mostly Scottish ethnicity, nothing has come up. But I knew about her when I was twelve and I felt terrified that I might grow up to be a giantess like her and have to join the circus, as a teenage boyfriend once joked. So my height always had a shadow side that I didn’t fully understand until I wrote Big Girls Don’t Cry.

CSPF: What do you think people will find surprising about your memoir?

Susan: The idea that body size is a factor in shaping our identities like race, gender, class, and cultural background. Many of us, especially women, have insecurities about our bodies, but we may not realize just how much that makes us who we are.

“Speaking as a fellow oddball, I think that this is the best book about coming to terms with your differences from the norm—especially for women—that I’ve read. It’s insightful, honest, and adept. Definitely, one of a kind.”

—Jane Smiley, Pulitzer Prize Winner

Memoir Cover Reveal

An exclusive first look at the cover of my new memoir, Big Girls Don’t Cry: A Memoir of Taking Up Space with a Foreword by Margaret Atwood, releasing May 2025 with HarperCollins Canada and Beacon Press!

A memoir about what it means to defy expectations as a woman, a mother, and an artist, examining the expectations of women across generations using the lens of my unusual height as a metaphor for how women are expected not to take up space in the world. This book is for readers of Joan Didion and Gloria Steinem and listeners of the podcast Wiser than Me.

To learn more about my upcoming book, visit this link for an exclusive Q&A with the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction about the differences between fiction and memoir and coming to terms with the differences that shape who we are.