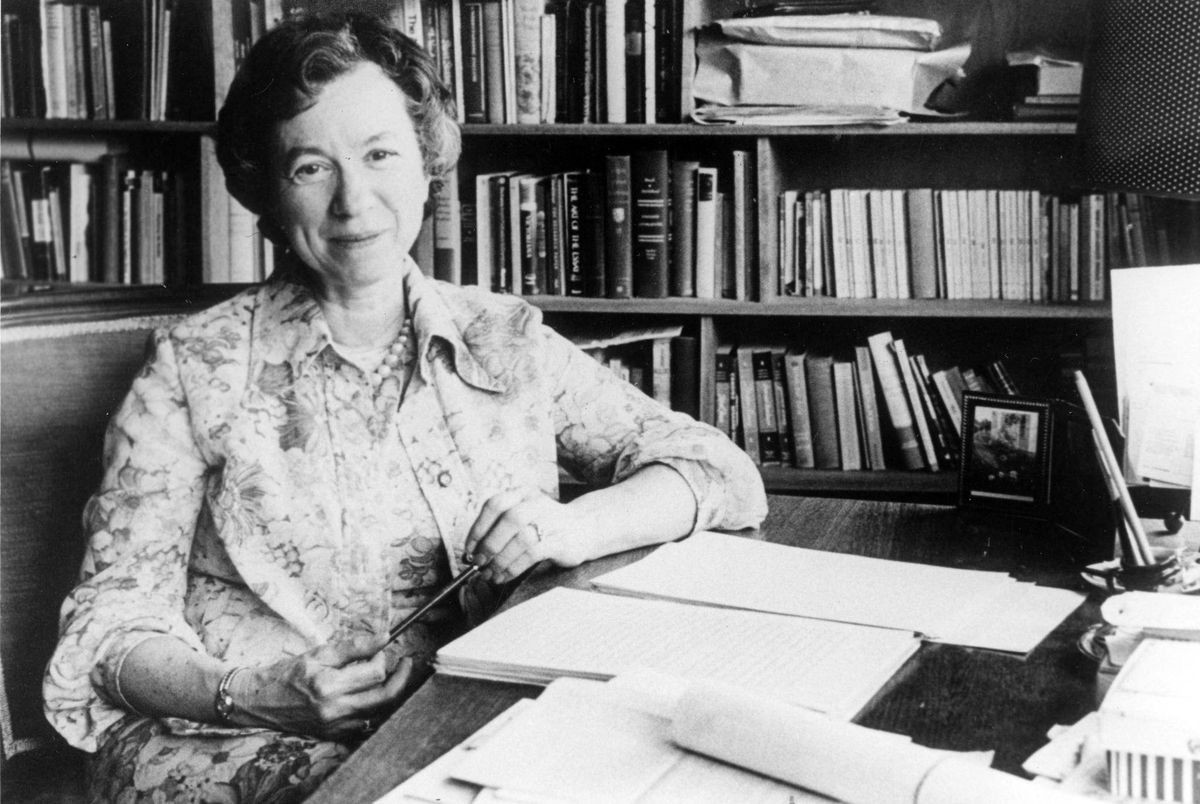

When you think of the giants in Canadian literature, chances are you think of writers such as Michael Ondaatje, Alice Munro or Margaret Atwood. Few readers these days remember Constance Beresford-Howe, who wrote ground-breaking novels about the struggle of women to be autonomous.

You may not know about her because she was shy. Or because, unlike some of these household names, she never won a Giller or the Man Booker Prize. But only a few decades ago, she wrote 10 feminist novels including The Book of Eve (1973), which critics have called a Canadian classic. And, recently, a dedicated band of her readers unveiled a beautiful bronze plaque in her honour in the Writers’ Chapel at St. Jax church in Montreal.

She is the 11th author to receive such a plaque, and I attended its unveiling because Constance Beresford-Howe was an encouraging mentor who taught me creative writing at McGill University. Back then, almost no Canadian colleges offered such a course.

Her colleague was Hugh MacLennan, whose workshops were known as Uncle Hughie’s bedtime stories since he was fond of long rambling conversations about American politicians and fellow authors such as Morley Callaghan. It was Beresford-Howe who could be counted on for tips on the craft of writing. She excelled at discussions of plot and character development. And she admired my writing, although she told me with a wry smile that my sex scenes were too graphic. Hugh MacLennan agreed.

As students of the sixties, we naturally felt we knew far more about sex and real life than our dignified mentors and we used to joke about being the first to write the toilet-bowl novel — a coup in literary naturalism that thankfully has never materialized. Later, I was startled out of my youthful arrogance when I read The Book of Eve and realized Beresford-Howe deeply understood the intimate relationships between men and women. Its saucy account of a 65-year-old woman walking out on an aging and crabby husband still stands up.

At the end of our undergraduate course, she wanted me to write a novel as my MA thesis. It was the chance of a lifetime to do graduate work with her. Yet, I turned down her generous offer because an ex-boyfriend had been stalking me on campus.

In 1967, I took a job as a reporter at a daily newspaper in Toronto. Two years later, Beresford-Howe moved to Toronto herself. Disturbed by the rising separatism in Quebec, she came with her husband, French teacher Christopher Pressnell, and their young son, Jeremy. When she applied for a teaching job at the University of Toronto, they turned her down. Jeremy thinks it was because she had taught at McGill, a rival university. For two long years, she had no teaching work and that’s when she wrote The Book of Eve.

Eventually, she took a teaching position at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute (now Ryerson University). And she went on to write novels such as The Marriage Bed and A Population of One. Her last novel, A Serious Widow, was published in 1991. Beresford-Howe couldn’t find a publisher for her next book. So she and her husband retired to the Suffolk village of Lavenham, where they lived for 25 years. She died in 2016 and her husband died two weeks later from cancer and a broken heart, her son says.

A writer’s legacy is an elusive thing. A few writers are so famous their work turns into memes, such as George Orwell‘s 1984 or Atwood’s handmaids, while some are known for influencing other writers. And then there is Beresford-Howe, whose readers are honouring her work and that of other deceased Canadian writers. The volunteers who install the plaques are led by retired English professor, Michael Gnarowski. His former student Karl Feige makes the plaques at a foundry outside Ottawa.

Coming back from the unveiling, I wondered what Beresford-Howe would say about a writer’s legacy. I bet she would give me one of her wry smiles.